NTC Veterans

Please see attached document to find out more about Port Alberni's Indigenous Veterans. A special thanks to Iris Sanders for presenting this information and our wonderful display at Wood!

Port Alberni, BC

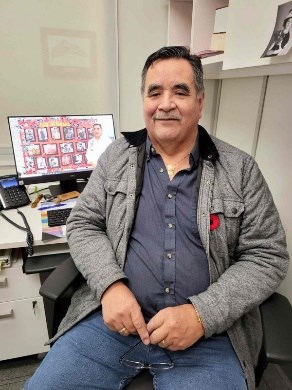

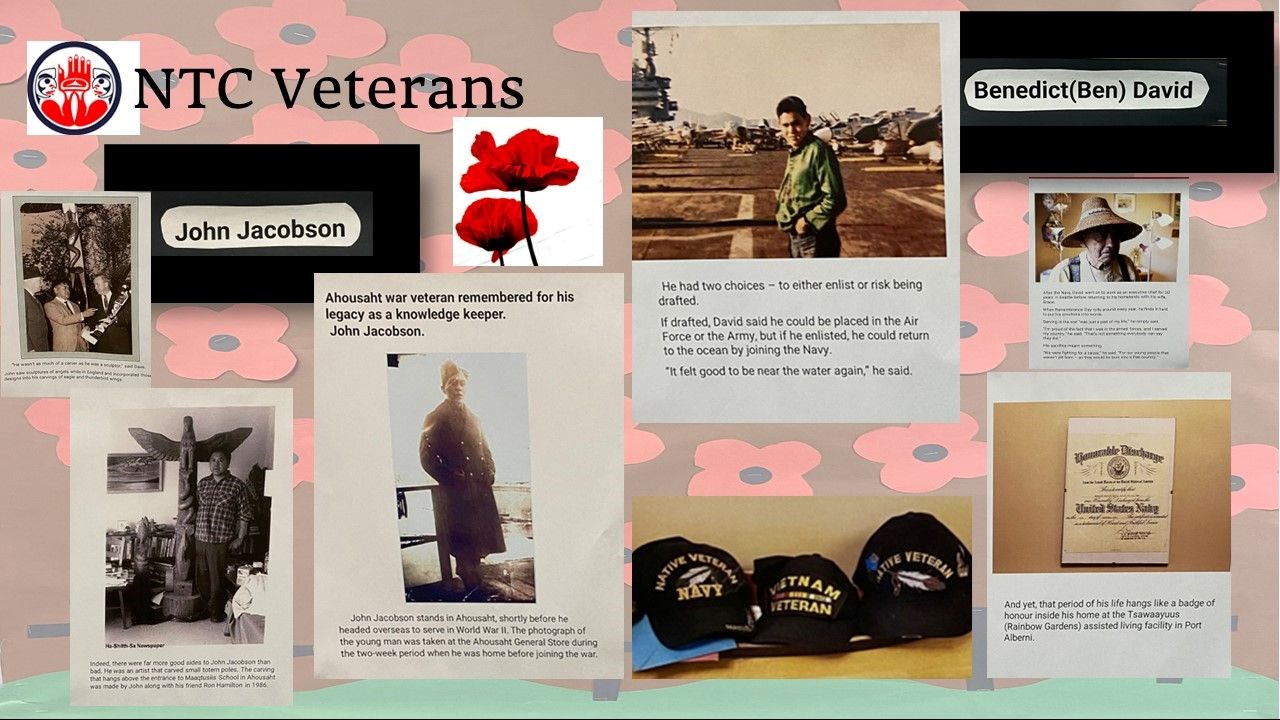

Benedict David has always felt an affinity towards the ocean. Born in a “little hole in the wall” cabin on Nootka Island, the surrounding Pacific waters were like his playground. He spent his childhood on Meares Island, off the coast of Vancouver Island, living in the remote Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation village of Opitsaht. David has vivid memories of trailing behind his mother through the forest to pick blackberries. “We were free,” he said. All of that changed when an Indian agent came to take David away in 1949. While trapped at Christie Residential School on Meares Island for seven years, the views of the ocean became David’s only reprieve. He was merely eight years old when the sexual abuse, beatings, and starvation began, and likens the experience to a war. “I went through hell in school,” he said. “You never ever forget what happened to you in school.” After “serving” time at residential school, David’s family relocated to the United States, where he completed high school. He was just getting settled into his new life in Yuma, Arizona, before the Vietnam War knocked on his door.

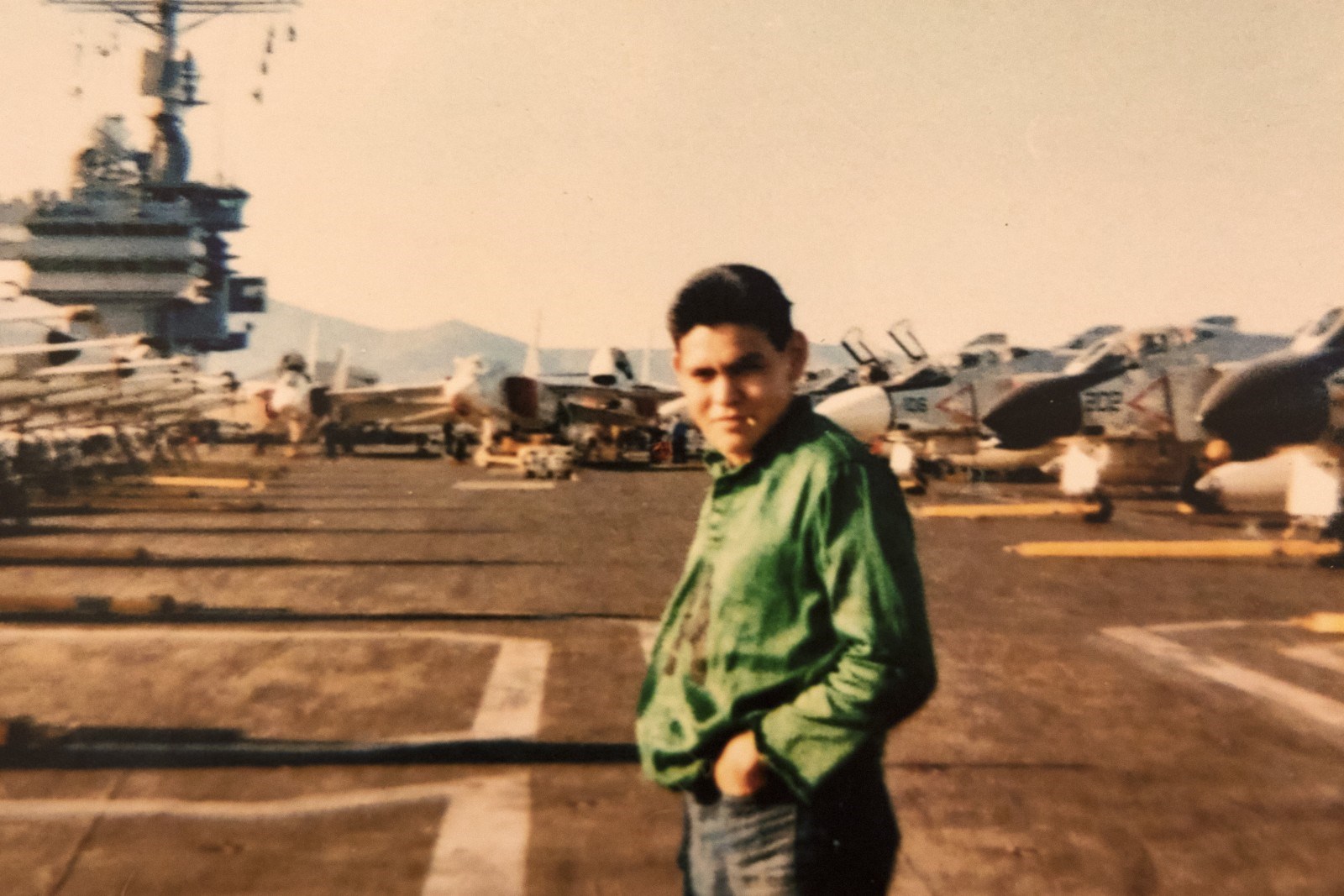

He had two choices – to either enlist or risk being drafted. If drafted, David said he could be placed in the Air Force or the Army, but if he enlisted, he could return to the ocean by joining the Navy. “It felt good to be near the water again,” he said.

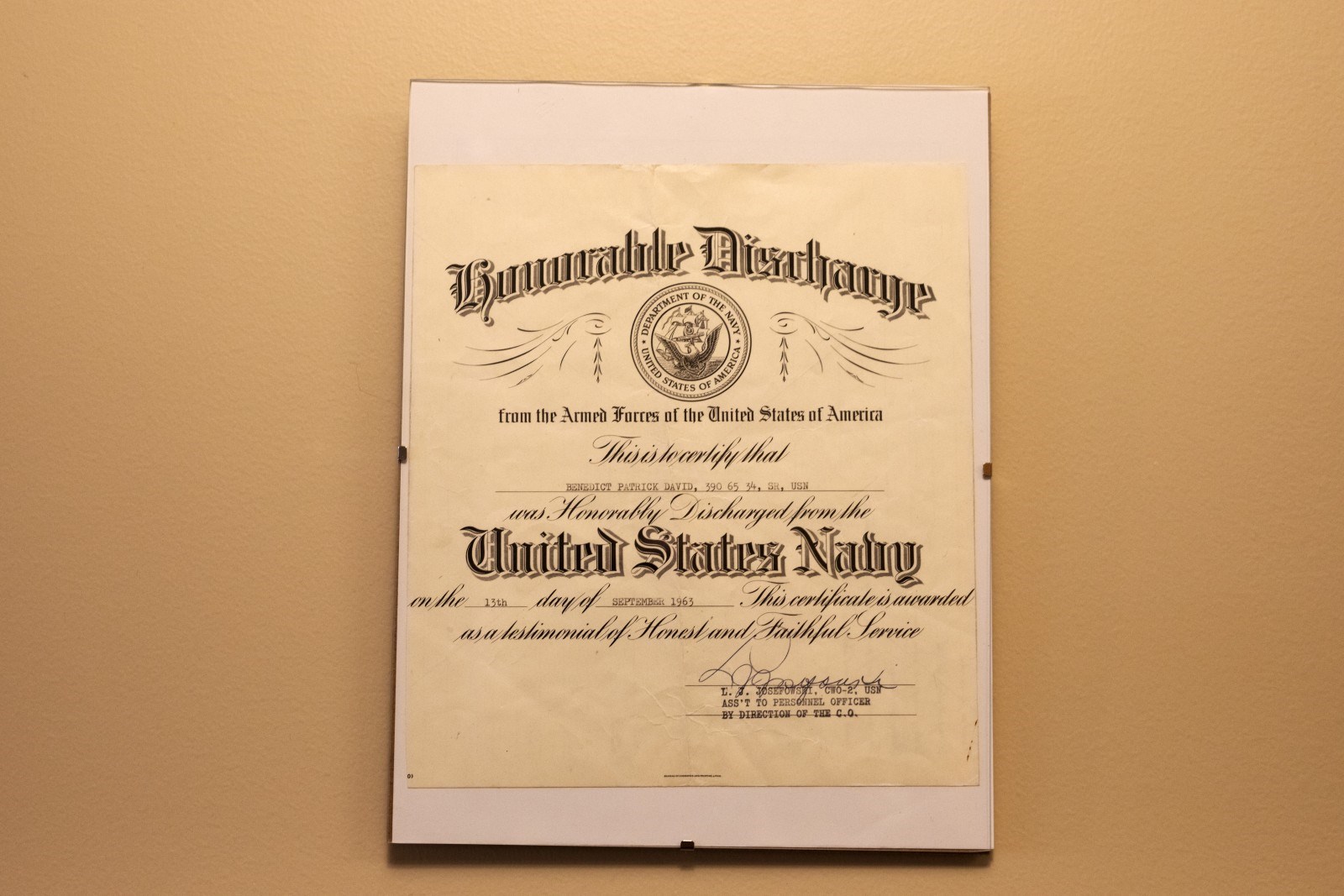

Having already endured a “war” at residential school through “brutal” beatings and torture, David said he was able to “tolerate” what he saw while serving two tours during the Vietnam War. In some ways, he said, residential school prepared him for it. “Vietnam is not a good experience for anybody,” he said. And yet, that period of his life hangs like a badge of honour inside his home at the Tsawaayuus (Rainbow Gardens) assisted living facility in Port Alberni. The 79-year-old’s collection of veteran hats are lined on his kitchen table. Above them, his United States Navy honourable discharge certificate is centred on the wall. It’s a period of his life not many people know of, he said. In part, because he finds it difficult to speak about.

“It was pretty heavy stuff,” he said.

After the Navy, David went on to work as an executive chef for 30 years in Seattle before returning to his homelands with his wife, Grace. When Remembrance Day rolls around every year, he finds it hard to put his emotions into words. Serving in the war “was just a part of my life,” he simply said. “I’m proud of the fact that I was in the armed forces and I served my country,” he said. “That’s not something everybody can say they did.” His sacrifice meant something. “We were fighting for a cause,” he said. “For our young people that weren’t yet born – so they would be born into a free country.”

Ahousaht war veteran remembered for his legacy as a knowledge keeper.

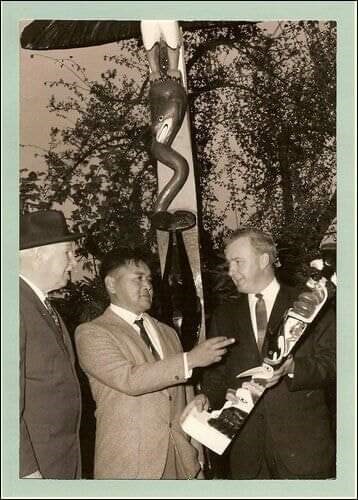

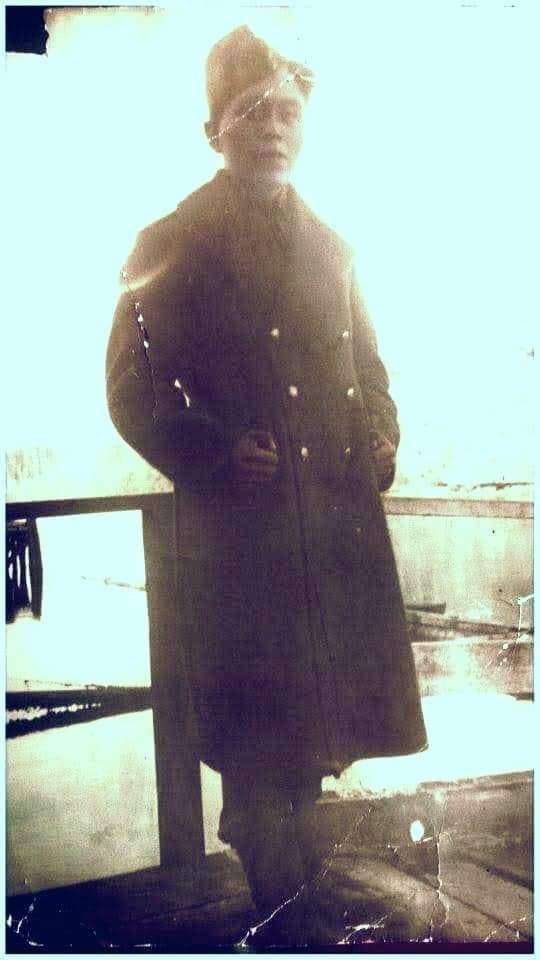

John Jacobson stands in Ahousaht, shortly before he headed overseas to serve in World War II. The photograph of the young man was taken at the Ahousaht General Store during the two-week period when he was home before joining the war. He was home before joining the war.

Ahousaht, BC

“When you are a knowledge keeper you gotta share it at every opportunity, and don’t expect anything back except maybe a cup of tea,” John ‘Smitty’ Jacobson advised his nephew, Dave Jacobson before his passing in 1986. John Jacobson was born September 16, 1922, to George and Nellie Jacobson of Ahousaht. From an early age he was taught to be a knowledge keeper and he collected as much information as he could, from family genealogy, cultural teachings and songs to art and classical music. While John was married to former schoolteacher, Joan, he never had his own children. He shared his knowledge with anyone willing to listen, many times with his nieces and nephews. According to Dave, his uncle John chose to enlist in the Canadian Army at a young age. “He did his training somewhere on the mainland, the prairies,” said Dave. When he was done training he was given two weeks to go back home before shipping out to Europe. “I guess they were sending them home to say goodbye to their families,” Dave speculated. The photograph of a young John Jacobson in uniform was taken at the Ahousaht General Store during that two-week period when he was home. “He didn’t talk about the war – he didn’t talk to family about it,” said Dave.

Instead, John had two trusted friends that would take his late-night or early-morning calls.

According to Dave, he’d make those calls and talk about his experiences and the trauma. Those friends were the late George Watts of Tseshaht and a trusted friend from Hupacasath. “There would be no goodbye, when he was done talking, he would simply hang up the phone. When the phone went dead, that’s when they knew he was done,” said Dave. While Dave was never told about what his uncle went through, he acknowledged that there was some trauma. Back then, he said, there was no emotional supports in place for war veterans. Many turned to vices and addictions to cope – and for his uncle John, it was alcohol.

“He could go many months without drinking but when turned to alcohol, he could go for days,” Dave remembered. He believed it was during those binges that his uncle was reliving and feeling his pain. “Then he’d sober up and he’d be good for a while,” said Dave. Indeed, there were far more good sides to John Jacobson than bad. He was an artist that carved small totem poles. The carving that hangs above the entrance to Maaqtusiis School in Ahousaht was made by John along with his friend Ron Hamilton in 1986.

“He wasn’t as much of a carver as he was a sculptor,” said Dave.

John saw sculptures of angels while in England and incorporated those designs into his carvings of eagle and thunderbird wings.

John was born in a time where it was important to commit to memory the things he learned, from family history to songs. He was the first one in Ahousaht to own a recording device. It was a reel-to-reel tape recorder that he used when he spoke to elders. “He talked to elders a lot about mułmimc, family roots. No matter where he went on the coast, he could always tie people back to Ahousaht through their family roots,” said Dave. In addition to his genealogy knowledge, John amassed a huge collection Nuu-chah-nulth songs. The tapes that he made of oral histories and songs are now at the Royal British Columbia Museum archives. “Anybody can access them…late (Dr.) George Louie transcribed a lot of the tapes. His notes are on yellow legal pads at the museum,” Dave shared.

When John got back from the war, he and his fellow Ahousaht veterans were no better off than they were before they left. While mainstream veterans were given tracts of land in exchange for their service, Aboriginal war veterans were given certificates of possession for parcels of land on reserve, something they already had a right to as Ahousaht members. According to Dave, Phillip Louie, Frank Williams and John Jacobson were given certificates of possession for land on reserve in Ahousaht, but away from the main village at the time. Williams traded his lot for one in the village while Phillip Louie gave an elder couple permission to build on his lot.

“The lots were too far away from the village for them to use,” said Dave.

Today, those parcels of land are along the shoreline, starting from Mattie’s Dock to a small house that belonged to Winona Thomas and her husband. The village has grown up around the lots. Another difference in the treatment of Indigenous war veterans was access to grants to get started in life. Most veterans got grants but Indigenous veterans were offered loans, according to Dave. “Uncle borrowed money to buy a fishing boat and he had to pay it back,” he said. But John didn’t let anything hold him back. He took what he learned from abroad and brought it home to Ahousaht. He was one of the first Ahousahts to attend university, spending a year at the University of Arizona. "He always sought knowledge and though he never had children of his own, he always talked to me,” Dave recalled.

He was generous with his knowledge and reminded his nephew to be generous with his teachings.

“You gotta share it at every opportunity and don’t expect anything back…be grateful that you have the ability to share these things,” John told Dave. “So that’s what I do today, share what I know.”

For his many contributions to the preservation of history and his service in the military, John Jacobson was honored by Nuu-chah-nulth-aht and the Canadian Coast Guard when a new CCG patrol vessel John Jacobson was named in his memory back in 1991.

John’s wife, Joan, was there with Jacobson’s family and friends for the CCG dedication ceremony back in 1991. Joan passed away in Port Alberni in 2020.

The CCG vessel John Jacobson was stationed in Esquimalt and was in service until 1999, when it was sold and renamed Coriolis II. It is now in Quebec.

Dave said that the Jacobson family were grateful to the NTC and the Government of Canada for the honor bestowed upon their uncle, acknowledging that he and his contributions were important.

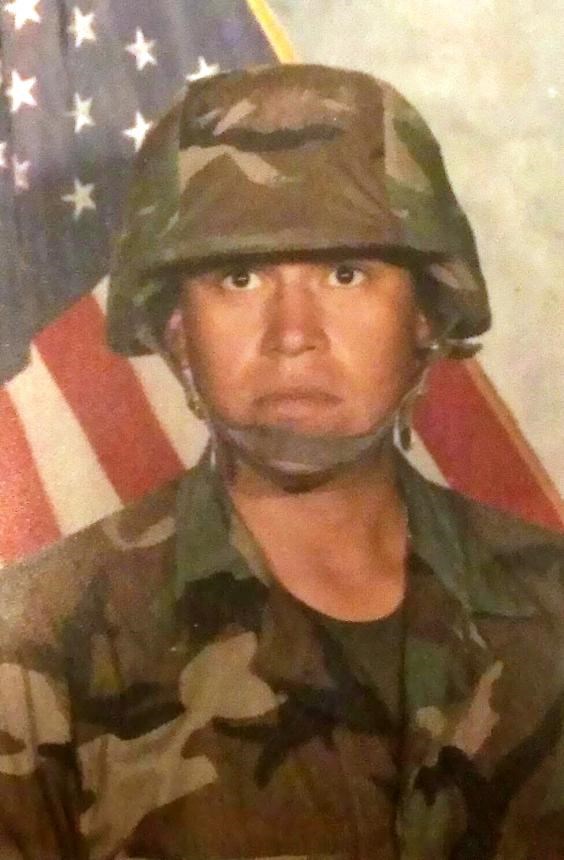

James Rush, Tseshaht, served for the United States in the Gulf War from 1990–1991.There are at least 25 known Nuu-chah-nulth war veterans, including those that were enlisted with the U.S. Forces.

Canada

Veterans Affairs Canada is honouring aboriginal men and women in uniform for their contributions and sacrifices. Nov. 8 is National Aboriginal Veterans Day.

In Manitoba, Michel Doiron, Assistant Deputy Minister at Veterans Affairs Canada, joined students of the Aboriginal Community Campus at the Centre for Aboriginal Human Resource Development this morning for a commemorative ceremony to honor Canada’s fallen indigenous heroes and veterans.

Doiron laid a wreath at the commemorative ceremony on behalf of Veterans Affairs Canada.

According to Veteran’s Affairs Canada, this event brings together people of all ages, including veterans, youth and indigenous people to pay tribute to the many brave indigenous men and women in uniform—past and present—who have made great sacrifices to serve Canada and defend our values.

“Indigenous veterans have served Canada with pride and distinction, and their dedication continues today in military and humanitarian operations around the globe. The Government of Canada, along with the rest of the country, are immensely grateful for their contribution,” reads a Veteran’s Affairs Canada news release.

“Today, we remember as many as 12,000 courageous First Nations, Inuit and Métis people who served Canada in conflict and peace support missions throughout the 20th century, with more than 500 who made the ultimate sacrifice,” said Seamus O’Regan, Minister of Veterans Affairs and Associate Minister of National Defense. “We honor the contributions made by all Indigenous people while serving, such as Manitoba native Sgt. Tommy Prince—one of Canada’s most decorated soldiers who exhibited extraordinary bravery and dedication to this country.”

According to an online listing called Aboriginal Veterans Tribute Honour, there are at least 6,600 Aboriginal war veterans that served in the Canadian Forces in various wars over the past 100 years.

There are at least 25 known Nuu-chah-nulth war veterans including those that were enlisted with the U.S. Forces.

James Rush, Tseshaht, is one of the U.S. war veterans that served in the Gulf War from 1990 – 1991.

“I was a machine gun squad leader during Desert Storm,” Rush told Ha-Shilth-Sa. “The USMC gave me a chance to travel through Asia. I went to Okinawa, the Philippines, Bali, Surbaya and Jakarta. I was in the first combat ready unit in Saudi Arabia for Desert Shield and we were the first ones into Kuwait City in Desert Storm. I was honorably discharged in 1992.”

Upon his return home he was given a new name. “I got the name Subits-ulth, meaning Sand in the Face, after Desert Storm,” he shared.

Rush resides in Seattle, Washington.

Watch Ha-Shilth-Sa in the coming days as we pay tribute to Nuu-chah-nulth veteran’s on Remembrance Day.

Some facts to ponder on this day of remembrance

In the two World Wars, First Nations people were exempt from conscription, were not considered “citizens” of Canada and did not have the right to vote.

Despite this:

4,000 First Nations men volunteered for service in WWI and over 300 died.

20,000 First Nations volunteered for service in WWII and over 200 died.

These numbers represent about 30% of First Nations men eligible to serve.

To serve in the Canadian Air Force or Canadian Navy you had to be “of pure European descent” although this was rescinded in 1940 for the Air Force and 1943 for the Navy.

Corporal Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwa from Parry Island, Ontario, was the most decorated First People’s soldier in WWI. He was a skilled sniper and trench raider and received the Military Medal 3 times. He returned to become Chief of the Parry Island Band.

Thomas George (Tommy) Prince, an Ojibwa from Manitoba, is Canada’s most decorated Aboriginal war veteran. After spectacular acts of bravery and cleverness, in full view of German soldiers, and critical reconnaissance missions he received the American Silver Star and six service medals. He was awarded the Military Medal for Gallantry by King George VI in 1945. When he came back to Canada he was refused the same rights as other returning veterans and couldn’t find work so he reenlisted and served in Korea.

There has been a concerted effort by First Nations and Metis groups to gain compensation for all the returned aboriginal veterans who were denied veteran’s rights and pensions after their years of service.

So far, success has been limited.

During World War I, women were permitted to vote as a proxy for their father, husband, brother or son who was serving in the Canadian Forces although they had no right to vote themselves. Women were given the right to vote in Federal elections in 1919, although this right was not ratified in Quebec until 1940. Women were granted status as “persons” in 1929, which meant they could run for elected office.

First Nations people were not given the right to vote and run in Federal elections until 1960.

Aboriginal Veterans Day began in 1994 in Manitoba to honour the contributions of First Nations and Metis people who served in the Canadian Military. In 2001 the National Aboriginal Veterans War Memorial was unveiled and dedicated in Ottawa, and commemorative ceremonies are now held in many communities in Canada on November 8th.

Remember and honour the sacrifices of all warriors who fought for our rights as Canadians to freedom and equality and trust that we can work towards a day where all men, women and children in Canada do have equal rights, respect and opportunities.

“A warrior is challenged to assume responsibility, practice humility and then centre his or her life around a core of spirituality. I challenge today’s youth to live like a warrior.”

Billy Mills – 2nd Native American to win an Olympic Gold Medal (10,000 m. Nagano, 1964)"